DISPOSAL ORDER

internal field account from corrective operations, part I

May Season Studio Archives

by Gintare O.

The email came through at 7:42 a.m. Early, in my opinion. Not early enough to be urgent, but early enough to signal someone higher up had already been thinking about it for a while.

It was addressed to Henry, our manager, with the usual layer of corporate politeness laid on thick.

Subject: Wrap-Assist L12 Program Termination

Effective immediately, all remaining prototype units from the L12 program are to be decommissioned and removed from active inventory. Hardware is classified as non-salvageable, non-returnable, and non-usable.

Please coordinate disposal per existing agreements.

Thank you for your help.

Henry printed the email anyway. He always did, even though everything lived in the system. He liked having something physical when the work crossed into the kind of space that didn’t technically exist but still needed doing.

He slid the page across the break room table to me and Merrit while the Keurig made a sound like it was reconsidering its life choices.

“New assignment,” he said. “R&D cut a project.”

Merrit glanced at the subject line and raised an eyebrow. “Gift wrap.”

“Automatic gift wrap,” Henry corrected. “Consumer concept. Holiday assist. It didn’t work out.”

“That tracks,” Merrit said. “Did someone finally get taken out by a bow?”

Henry ignored him. He always ignored Merrit’s first joke. Let it burn itself out.

“There are thirteen units,” Henry continued. “All prototypes. They want them decommissioned and removed today.”

The email didn’t mention injuries. It never did. “Non-salvageable” was corporate shorthand for too risky to sell.

“Where are they,” I asked, already pulling out my notebook.

“Joliet testing facility,” Henry said. “They’ve been isolated there since the last incident.”

“Incident,” Merrit repeated.

Henry sipped his black coffee and didn’t elaborate.

“Load them first,” he said. “We’ll review disposal options once they’re under our control. And don’t wear your disposal jumpsuits through the main hallways. He paused, then added, “People get nervous when they see you in them.”

Contractor badges had the black-and-orange stripe. Regular employees were white. Everyone noticed, even if no one said anything.

We took the van.

From the outside, May Season Studio looked expensive and stable. Glass, steel, landscaping trimmed on a schedule. On the inside, departments like ours made sure it stayed that way.

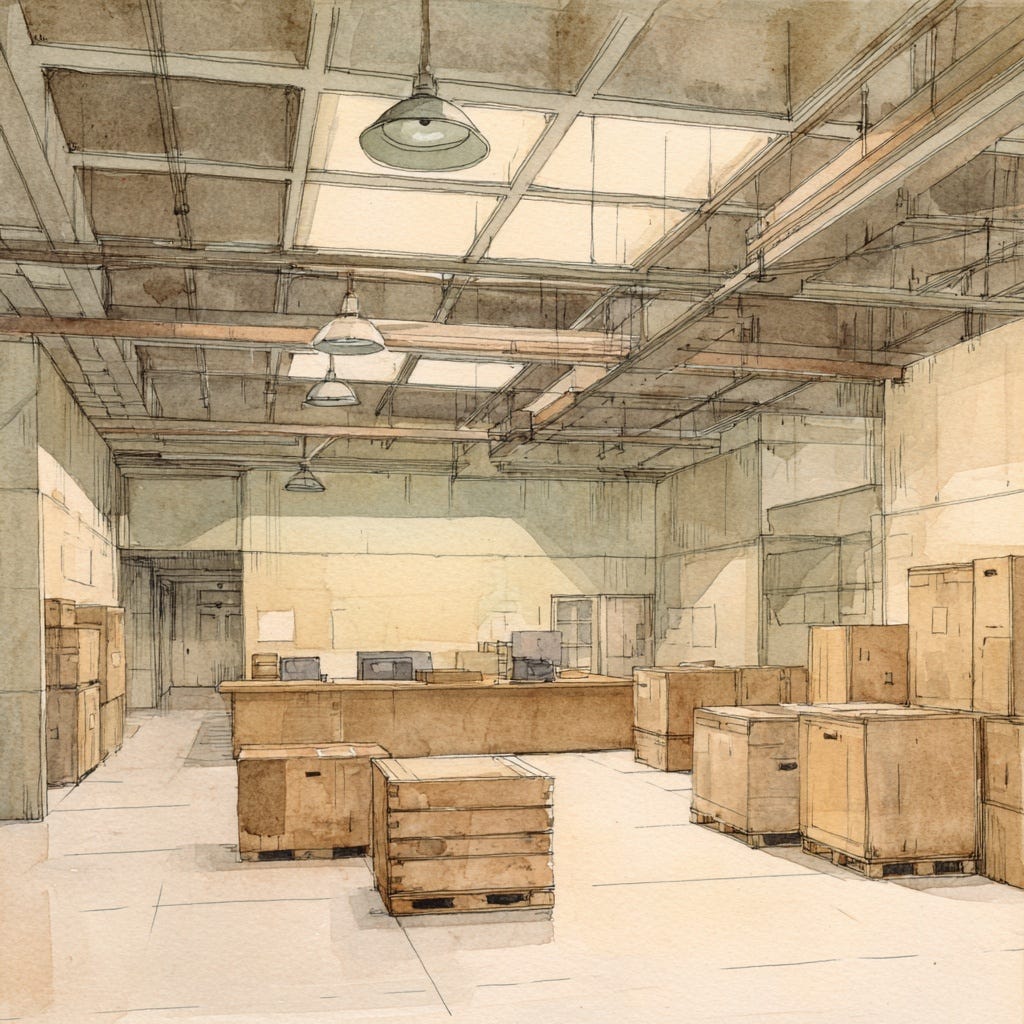

Joliet was about forty-five minutes down I-355 and west on I-80. The testing facility looked like a shipping warehouse if you didn’t know better. No windows. Minimal signage. The logo was small enough to ignore.

The dock door was half open.

Inside, the air was cold in a way that came from concrete and fluorescent lights, not weather. A single R&D engineer waited near a stack of crates pushed against the far wall. Badge on a lanyard. Tablet in hand. The kind of engineer who had learned not to react to things anymore.

“L12 program,” he said, nodding toward the crates. “Wrap-Assist modules. Prototypes only. Tagged and logged.”

He didn’t offer his name. We didn’t ask.

The crates were standard equipment size, but the labels weren’t.

WRAP-ASSIST L12

NON-OPERATIONAL

DO NOT PLUG IN

Each crate carried a small red sticker in the corner.

INCIDENT REPORT ON FILE.

I walked the perimeter of the nearest crate, reading everything twice. The pallet beneath it had scrape marks, like something inside had shifted more than once. A strip of metallic ribbon poked out through a gap in the slats, cut clean like it had been sheared deliberately.

“Any handling notes,” I asked.

“Unplugged, they’re inert,” the handler said. “Power was cut after the curtain event.”

“Curtain event,” Merrit echoed.

The handler paused just long enough to be noticeable.

“It wrapped the room,” he said finally. “Floor to ceiling. Curtains, cables, fixtures. One of ours was inside. He lived.”

“Lucky,” Merrit said.

“Legal didn’t think so,” the handler replied. “After that, the project went from innovation to liability.”

He checked something off on his tablet.

“They’re already logged out under your manager’s cost center,” he added. “As far as the system’s concerned, they’re gone.”

Which meant if they stayed here, it would look like theft. On paper, they no longer existed.

“Any others,” I asked. “Loose units. Labs.”

“Thirteen shipped. Thirteen here,” he said. “What happens next isn’t my problem.”

He walked away without looking back.

We started loading.

The first crate squeaked when the pallet jack slid underneath. Not loud, but sharp enough to echo. The crate felt heavier than it should have. R&D always overbuilt. Pride, mostly.

“Feels like a coffin,” Merrit said.

“Don’t anthropomorphize,” I replied, steadying the load.

We lined up the first four in the van, strapped them down, and went back for more. By crate seven, the pattern stopped being interesting. Same labels. Same red sticker. Same scrape marks.

Crate nine had writing scrawled on the side.

NOT FOR DEMO FLOOR.

Someone had drawn a small angry face beneath it.

“What did this one do,” Merrit asked.

“Probably embarrassed the wrong director,” I said.

Crate eleven left a smear of fine metallic glitter on the dock floor when we moved it. Not the cheap kind. The kind that sticks forever.

I looked up. Ribbon fragments were tangled in the ductwork above, curled like decorations no one bothered to remove.

“You seeing this,” I said.

“Festive,” Merrit replied.

“No one in R&D decorates,” I said. “Not voluntarily.”

By the time we reached twelve, the room felt wrong. Not dangerous. Just unwilling to let go.

“That’s twelve,” Merrit said.

“Thirteen total,” I reminded him.

The last crate sat apart from the others. Slightly smaller. Same warnings. Same red sticker.

Someone had written a number on it in thick black marker.

13

No jokes. No doodles.

As we approached, I heard it. A faint, uneven ticking from inside. Not mechanical in the usual sense. More like something trying to keep time without instructions.

“You hear that,” Merrit asked.

“Yes.”

“It’s unplugged.”

“Yes.”

The ticking stopped. Then started again, off rhythm.

I slid the pallet jack under the crate. It resisted for a moment, then lifted. The ticking sped up, then stopped completely.

“Like it knows,” Merrit said quietly.

“It doesn’t know,” I said. “It wraps.”

We loaded it last, centered, strapped tighter than the others. When the doors closed, the sound dulled to a faint tap through the metal.

Henry called as we pulled onto the highway.

“You have them,” he asked.

“All thirteen.”

“Good. Bring them in through the delivery entrance. No need to advertise.”

The call ended.

The van hummed along the road. Traffic thinned. The sky stayed flat. Somewhere behind us, just beyond the thin metal wall, something ticked softly at its own pace.

We didn’t talk.

That part came later, when disposal stopped behaving like disposal and started behaving like persistence.

For now, the job was simple.

Drive.

Unload.

Document.

Pretend the crates were just hardware.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Every large organization has a method for ending projects that no longer serve a purpose. Sometimes that ending is quiet. Sometimes it involves inventory, paperwork, and third-party contractors whose job is to make sure unfinished ideas do not linger longer than they should. This entry marks Part I of V in a multi-part account documenting the Wrap-Assist L12 program termination and its downstream effects. What follows is not an exposé or a warning. It is a record of standard procedure, logged the way these things usually are, before the rest of the work begins.

written and designed by gintare okrzesik, creator of may season studio — a fictional corporation exploring beauty, bureaucracy, and quiet corruption through narrative design.